The Second Italo-Senussi War

Mussolini particpating in the Great Parade, Benghazi 1934.

The Second Italian-Sanussi War, also known as ‘The Pacification of Libya’ took place between 1923 and 1932. This was a significant conflict between the Italian colonial forces and the Libyan resistance, led by the Sanussi order, under the leadership of Omar al Mukhtar, and was the period during which the Libyan genocide commenced1.

This war marked the most crucial chapter in the struggle for Libyan independence, as the Sanussis continued their fight against Italian imperialism and sought to preserve their cultural and religious identity. The resistance of local people to Italian colonisation, organised in their opposition by the Senussi warriors, was met with extreme brutality by the Italian military and culminated in the deaths of approximately a quarter of the estimated regional population of 225,0002. Furthermore, during this period, over 100,000 Cyrenaicans were expelled from their native lands, interned in desert concentration camps3, and their settlements ceded to Italian settlers4. Historian Ilan Pappe has estimated that up to half of the existing Bedouin population perished, either directly by violent tactics of the Italian military (which included the use of mass killings, chemical weapons and execution of surrendering combatants in violation of widely accepted rules of company engagement), or died indirectly through disease and starvation during their imprisonment in Italian run concentration camps5.

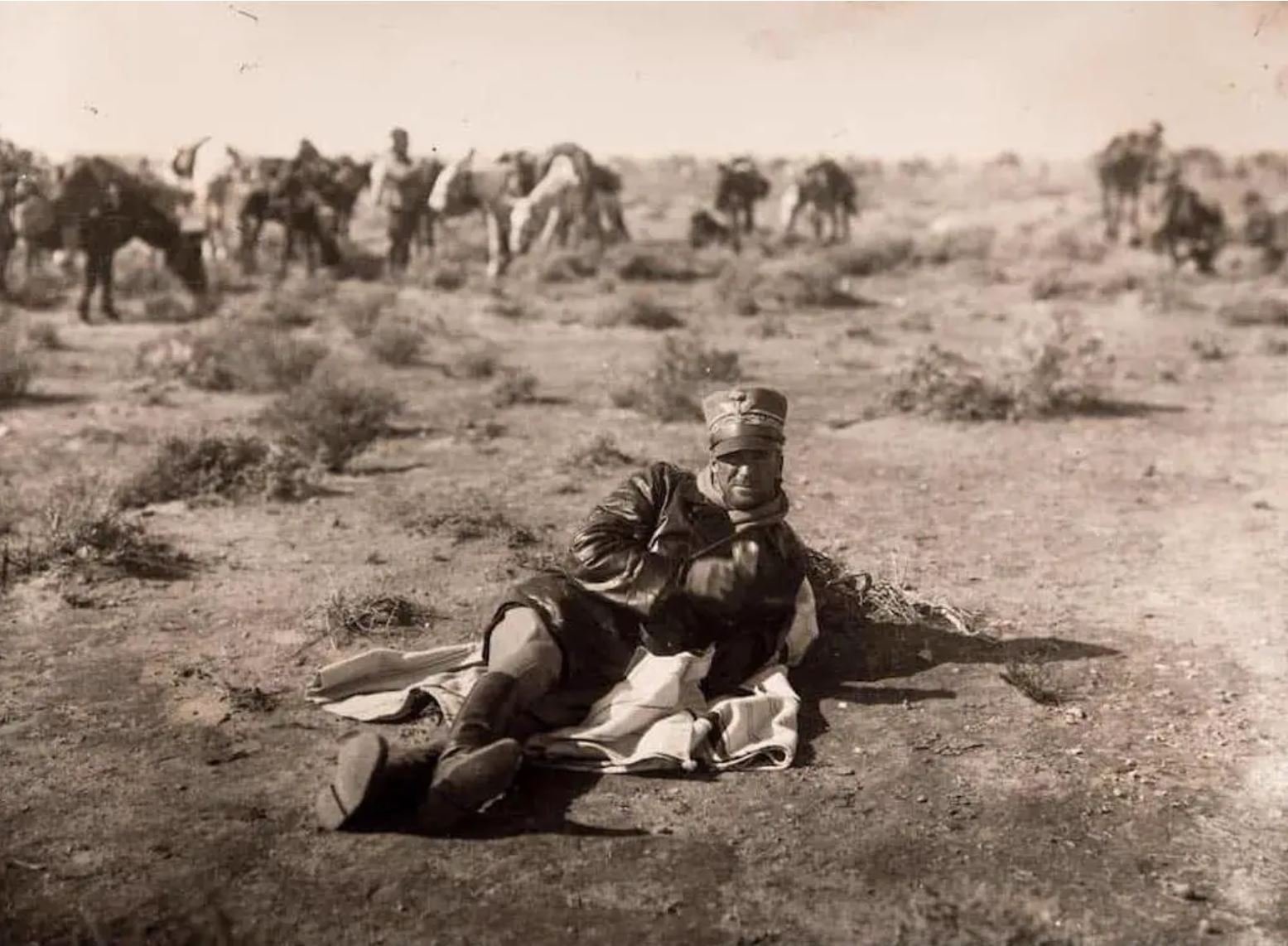

Omar Al Mukhtar with Libyan Mujahideen, circa 1920s

The fighting during the Second Italo-Senussi war between patriot mujahideen and the Italian militia, which had previously taken place across Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan, was now primarily fought in the Jebel Akhdar (Green Mountain) region of Cyrenaica, due to the Italians having taken hold of most other areas. As this region was a patriot stronghold, these battles culminated in intense and prolonged fighting between the parties, as Italian attempts to occupy the region were perpetually met with resistance from the Senussis6.

Background to the Second Italo-Senussi War

Towards the end of the Periods of Accords (1917-1923), which followed the 1917 signatures by Italy and the Ottoman Empire of the Treaty of Acroma, there followed in 1919, the Ottoman Empires signing of an armistice agreement, in which they ceded their claims over Libya, to Italy. Italy then issued the statutes named 'Te Legge Fondamentale' with both the Tripolitanian Republic in June 1919, and Cyrenaica in October 1919, these statutes provided locals with the right to joint Libyan-Italian citizenship, while permitting each province to have its own parliament and governing council. The Senussis largely supported this arrangement and Idris attended celebrations in Rome to acknowlege the settlement.

In October 1920, Italy and Cyrenaica signed the Accord of al-Rajma, which provided Idris with the title of the Emir of Cyrenaica7. Idris would receive a monthly sum by the Italian government, and the Italians would retain administration and policing duties of areas under Senussi control, with the Senussis also disbanding their military capabilities. However, the Senussis did not comply with this order, and by the end of 1921, relations had once again deteriorated between the Italians and the Senussis.

King Idris in Rome for the signing of the Al Rajma Treaty, October 1920.

Following the death of Tripolitanian leader Ramadan Asswehly, in August 1920, the region broke out in tribal disputes. By January of 1922, the Tripolitanians had formally offered Idris the oppurtunity to extend his rule over Cyrenaica to include Tripolitania, in the hope of settling civil strife. While the Senussis were concerned that unifying Cyrenaica and Tripolitania would breach the Treaty of Al-Rajma and strain relations with the Italians, they agreed to the proposal in November 19228. But, Idris soon came to fear retribution from the Italian goverment under the new fascist leader Benito Mussolini, and went into exile in December of 1922.

Before Idris was able to accept the new position as Emir of Tripolitania and consolidate his leadership, Mussolini had authorised the second campaign of reconquest.9

The Period of the Accords had seen the rise to power in Italy of the National Fascist Party (NFP) of Benito Mussolini, in Italy.

The NFP held the annexation of Libya to be of critical importance to the creation of a robust Italian empire. Consequently, Mussolini capitalised on incidents such as the alleged killing of Italian soldiers in Shar al-Shatt (Sciara Sciat in Italian) in 1911, to rally political support for a second military invasion of Libya.

Benito Mussolini talking to an Eritrean soldier of the Italian Army's colonial troops in Libya, 1934.

Shar al-Shatt (Sciara Sciat)

The battle and massacre at Shar al-Shatt, which lay on the outskirts of Tripoli, took place on the 23rd October 1911.

The battle occurred shortly after the Italian conquest of Tripoli on the 28th September 1911. Although the actual conquest of the city was executed swiftly, due to the late arrival of additional military forces, the Italian administration quickly lost control of the interior of Tripoli when groups of native Libyans, led by Officers of the Ottoman military, who were known as the ‘Young Turks’ staged a revolt. Locals were encouraged to infiltrate industries and companies owned by the colonists and to provide details of all males deemed suitable to bear weapons and able to participate in a jihad against the Italians. The locals also performed reconnaissance on roads, informing of Italian troops positioning and movements.

An Italian machine-gun section at Shara Shat oasis on the outskirts of Tripoli. A fierce assault by Turkish-Arab forces on October 23, 1911, overran two companies of Italian infantry and resulted in isolated reprisals against allegedly complicit local Arabs that, unfortunately for the Italians, alienated the local population.

It was with this information and the amalgamation of Turks and Arabs as a combined force that led to among others the Battle and Massacre of Shar al-Shatt, where the five hundred strong, IV Battalion of the 11th Bersaglieri Regiment of Colonel Gustavo Fara were ambushed and annihilated. It is reported that horrific injuries and torture was suffered. Approximately 210 Bersagleri were killed at the battle, with 290 surviving, only to be tortured and killed after surrendering to the jihadists at a local cemetery.

The Reconquest

The Italian reconquest of Libya began with Italian forces invading and securing the Sirte desert region between Tripolitania from Cyrenaica. The strategic occupation of approximately 150,000 kms square of the Sirte desert region was rapidly accomplished by the Italian army in a five month period, with the assistance of aircraft and motor transport11 effectively separated the rebel forces of Cyrenaica and Tripolitania12.

Vintage engraving of the Battle Of Sciara Sciat during the Italo-Turkish War, 1911.

Visit by Marshal Balbo to the workers, during the construction of the coastal road, Libya 1920. Alamy.

Tripolitania and Fezzan

Following the separation of rebel troops of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, the Italians were able to make rapid progress in the reconquest of Tripolitania. During this period the local local resistance fought many battles, but the ever increasing number of Italian forces, plus their use of land vehicles and aerial bombings of patriots and bedouins alike, left the resistance fighters struggling and their guerilla style attacks, so successful in rebuffing the Italians during their earlier campaign, had little effect13. Between 1923 and the end of 1924, the Italians were able to bring the entire region north of the Ghadames and Mizda regions of Western Tripolitania and northern Fezzan, under their control, essentially controlling an estimated 80 percent of the inhabitants of Tripolitania and Fezzan.

By 1930, the Italians had managed to conquer most of Fezzan, reaching Tummo in south Fezzan, where the Italian flag was then raised14.

Map of Italian pacification of Tripolitania and Fezzan (1922-1930).

Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica proved to be, by far, the most challenging region for the Italians to reconquer. On the Eastern front, the Italians were able to make gains in the flatter regions of northern Cyrenaica, but were unable to progress into the mountainous forests of the Jebel Akhdar region, which was the stronghold of the mujahideen resistance fighters of Omar Al Mukhtar.

By the end of 1924, the Italians had managed with great effort to conquer the western end of Jebel Akhdar, pushing Omar and his men eastwards, into the gorges and heavily wooded areas of the central plateau, where they had some protection from air reconnaissance, and armoured vehicles. From this position, Omar continued leading raids on Italian troops who were attempting to push their forces further into the patriot strongholds. Consequently, the Italian army, however much larger and better equipped, still found it difficult to subdue the patriot forces, who launched unexpected attacks on smaller columns and dispersed into the forested hills of Jebel Akhdar 15.

A road in the mountains outside of Benghazi during the Italian occupation, 1930s. From the Commissariato per il Turismo in Libya.

Italian Savari Battalion in Libya, 1925.

‘With Mussolini in Tripoli (1926), British Pathe Archival Footage.

Title: "With Mussolini in Tripoli - first pictures of Italian Dictator since attempted assassination (note his bandaged nose)". FILM ID:490.13. Mussolini visits following the conquest of Tripoli by the Italians.

In the early months of 1926, the Italians took the small oasis city of Jaghbub, which was the historic seat of the Sannusi Order and the final resting place of its founder. The capture of Jaghbub, was met with little to no resistance, and was handed over to the Italians by the Shaikh of the Zawiya. The Italians were under the misapprehension that the occupying of the sacred city would bring an end to Omar's influence on the bedouins, and also anticipated that Omar would retaliate. In an attempt to pre-empt and ward off such a retaliation by the resistance fighters, the Italians staged a powerful offensive on the central plateau, destroying the patriots' crops and either killing or capturing their livestock, including sheep, camels, goats and horses16.

Battles and skirmishes continued throughout Northern Cyrenaica, and by the spring of 1927, while both Italian and patriot forces suffered losses, the majority of deaths had been incurred by Omar and his men, with the Abid and Bara’asa tribes being most critically affected. This dealt a severe blow to Omar as these two tribes were his most steadfast supporters and had contributed the strongest warriors. Consequently, Omar and his men dispersed into heavily wooded areas, including the Wadi Mahajja region and the area south of Jarvis al-Abid. Omar recognised that the situation which he and his remaining men faced had become nearly insurmountable, and agreed to meet with the Italians in an attempt to negotiate a peaceful outcome17.

Savari: Libyan soldiers of the army of the Kingdom of Italy in Libya, 1920-30.

Treaty Talks

Discussions and meetings followed between the two parties. Over the months, Omar met often with officials from both sides, but negotiations always failed, with neither party able to reach agreements on various aspects of the treaties18. However, on the 19th June 1929, a meeting took place at Sidi Rahouma between the two sides. In attendance were Governor Pietro Badliogo-the Governor of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica; Vice-Governor Domenico Siciliani, Omar al Mukhtar, al -Sharif al-Gharyani and Ali Basha al-Abeedi, who were leading figures of the Libyan resistance, along with guerilla leader Sidi Fadil ‘Umar. Also present at the meetings, was Sayyid al-Hasan al-Khattab, the sole representative of the Senussi family still in Libya, who accompanied and fought alongside the Patriot forces on the plateau. At this meeting Omar presented his final terms, and showed willingness to accept an agreement, whereby he promised peace and the recognition of Italian sovereignty over the whole of Cyrenaica, provided that the following terms were met19.

(i) No Italian interference in the issues of religion, and the right for the muslim community to implement Shariah Law as the source of legal justice, within the muslim community, rather than any governmental laws, regulations or court orders stemming from the Italian rule20; (ii) Arabic remaining the official language of Libya, accepted by all government offices; (iii) The opening of special schools offering Islamic courses and study disciplines; (iv) Amnesty for and release of all political prisoners and detainees; (v) The removal of all Italian military bases and forts built in Cyrenaica by the Italians during the war.

Following this meeting both parties appeared to agree to the conditions set out, and a two month truce was put into place, ostensibly to allow time for the policies to be looked over and agreed upon, by the higher Italian authorities. However, Badliogo, had no intention of honouring his promise and immediately set about ways to demoralise and cause dissension amongst Omar and his mujahideen. The truce, which actually lasted for five months, finally ended in November 1929, when, unable to reach an agreement on the implementation of the original conditions, set by Omar, the Italians persuaded Sayyid al-Hasan Sannusi to travel to Benghazi and enter into an agreement with the Italians. This agreement greatly favoured the Italians, and was also very beneficial to himself. The agreement was at once rejected by Omar, which led to the desertion of Omar by Sayyid al-Hasan Sannusi and his followers, who were named ‘The Flour Army’ by Omar and his men, who accused them of selling out to the Italians for extra rations21.

Omar Al Mukhtar at the Sidi Rahouma negotiations 1929. From left Siciliani, Fadil Bu Omar, Said Hassan Sinusi, SE Badoglio, Omar al Mukhtar.

Italian Colonial Troops headed by Amadeo, Duke of Apulia.

Resumption of Fighting

Fighting between the Italian forces and the Patriots resumed in November 1929 and Sayyid al-Hasan and his men, who had been kept under constant surveillance by the Italians, but otherwise left alone were decimated in battle on the 8th January 1930, after having resisted attempts by the Italians to disarm them, leaving Sayyid himself no option but to surrender, along with his remaining men.

During the period in which the Treaty talks occurred, from February 1929 until the start of 1930, it was estimated that the patriot forces had lost approximately 800 more men, 2000 more camels and an immense quantity of cattle and other livestock, whereas the Italian army had lost only a very negligible amount of officers and troops, causing further imbalance in the strength of the warring parties.

On 18 January 1930, Omar and his men engaged in battle with the Italian army in Wadi Mahajjia in central Cyrenaica. Omar was, on this occasion, wounded but managed to escape23. By now, having lost all of their bases and the majority of their livestock, Omar and his men were living in perilous conditions in the forested area of the Jebel Akhdar mountains, situated between the Italian encampments at Jardas Jerrari, Sulantuh, Fadiyah and Khawalan.

Italian colonial army cavalrymen in Bengazi during the colonial occupation of Libya (late thirties).

It was at this time that Mussolini, tired of the continuing skirmishes between Italian troops and the patriot forces, appointed Rodolfo Graziani as Vice-Governor of Cyrenaica and commander of the Italian forces in Libya24.

General Rodolfo Graziani, “The Butcher of Fezzan”, Cyrenaica, Libya. c. 1931

FOOTNOTES.

E.E. Evans-Pritchard. The Sanusi of Cyrenaica. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1949. Pg.157.

Mann, Michael. The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2006. p. 309.

Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk. The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2010. p. 358.

“Second Italo-Senussi War.” Wikipedia, August 29, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Ital o-Senussi_War.

Pappé, Ilan. The Modern Middle East: A social and cultural history. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014.

“Second Italo-Senussi War.” Wikipedia, August 29, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Italo-Senussi_War.

Page, Melvin E.Colonialism. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2003. P749.

Ibid.

J.Wright. A History of Libya. Hurst & Co. London. London: 2012. p. 33.

Gerwarth, Robert; Manela, Erez. Empires at War: 1911-1923. Oxford: Oxford University Press.2014.

J.Wright. A History of Libya. Hurst & Co. London. London: 2012. p. 35.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid. pg 140.

E.Evans-Pritchard. The Sanusi of Cyrenaica. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1949. Pg 179.

Ibid .Pg.182.

Dr Ali Muhammad As-Salabi. Omar al Mukhtar - Lion of the Desert. London: Al-Firdous. 2014. Pg 77-92.

E.Evans-Pritchard. The Sanusi of Cyrenaica. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1949. Pg 182.

Ibid.

E.Evans-Pritchard. The Sanusi of Cyrenaica. Oxford: University Press. 1954. Pg.182-183.

Ibid.

Ibid.

E.Evans-Pritchard. The Sanusi of Cyrenaica. Oxford: University Press. 1949. Pg.187-188.