the libyan genocide

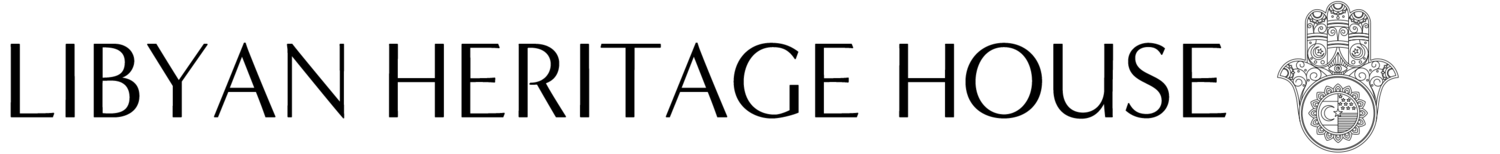

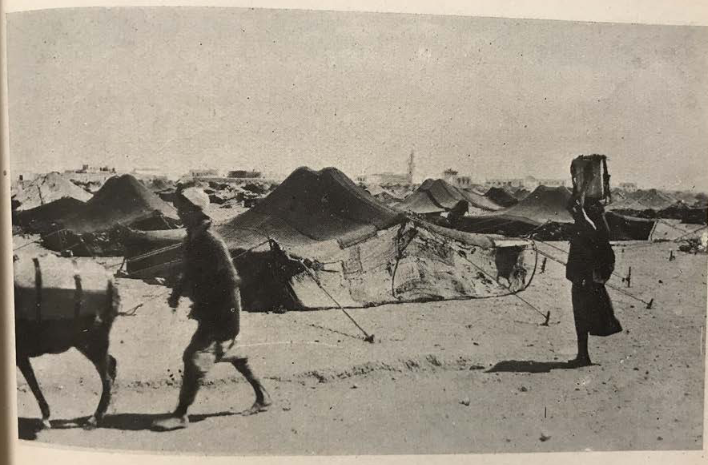

Distribution of soup at Al-Magroon concentration camp, which had circa 13,050 Libyan prisoners by 1931. compare Enzo Santarelli, et al: Omar al-Mukhtar: The Italian Reconquest of Libya. Darf 1986, p. 100

‘The Pacification of Libya’ took place towards the end of the Second-Italo Seunissi War1, after Mussolini tasked Rodolgo Graziani with the mandate of bringing the conflict to a final resolution, in 1929.

The resistance of local people to Italian colonisation, organised in their opposition by the Senussi warriors, was met with extreme brutality by the Italian military and culminated in the deaths of approximately a quarter of the estimated regional population of 225,0002. Furthermore, during this period, over 100,000 Cyrenaicans were expelled from their native lands, interned in desert concentration camps3, and their settlements ceded to Italian settlers4. Historian Ilan Pappe has estimated that up to half of the existing Bedouin population perished, either directly by violent tactics of the Italian military (which included the use of mass killings, chemical weapons and execution of surrendering combatants in violation of widely accepted rules of company engagement), or died indirectly through disease and starvation during their imprisonment in Italian run concentration camps5.

Graziani’s Strategy

Prior to Graziani’s appointment, the general strategy of the Italians had been to attempt to sow division between Libyans who had been subjugated or were otherwise willing to accept cooperation with the Italians (the sottomessi, meaning the 'subjugated' or the 'obedient' in Italian) and the resistance fighters: sotomessi were employed to assist the Italian army and, in some cases, served in it.

The strategy of dividing the local peoples was aimed at weakening the support base of the resistance fighters. Now, after the persistent failure of the military offensive to progress in Cyrenaica, the heartland of the resistance movement, Graziani moved to change their strategy. It had become increasingly clear that enforcing a strict separation between the two groups was not achievable, since the resistance movement was supported both materially and morally by the supposedly subjugated population. The civilians donated funds, weaponry, clothing and food to Omar Mukhtar's desert warriors. Some even made horses available to the fighters, ensuring the continuation of the resistance movement by Omar’s men, even if they themselves were considered sotomessi. Accordingly, the new strategy formed by Graziani and his advisors aimed to disempower the civilian base on which the resistance movement was, in fact, reliant upon 6.

Sotomessi: Libyan soldier of the army of the Kingdom of Italy in Libya, 1920s.

In a missive to General Graziani dated 20 June 1930, general Pietro Badoglio, stated, "As for overall strategy, it is necessary to create a significant and clear separation between the controlled population and the rebel formations. I do not hide the significance and seriousness of this measure, which might be the ruin of the subdued population...But now the course has been set, and we must carry it out to the end, even if the entire population of Cyrenaica must perish"7.

Pietro Badoglio, Italian general and politician. Badoglio supported of the placement of Cyrenaicans in concentration camps.

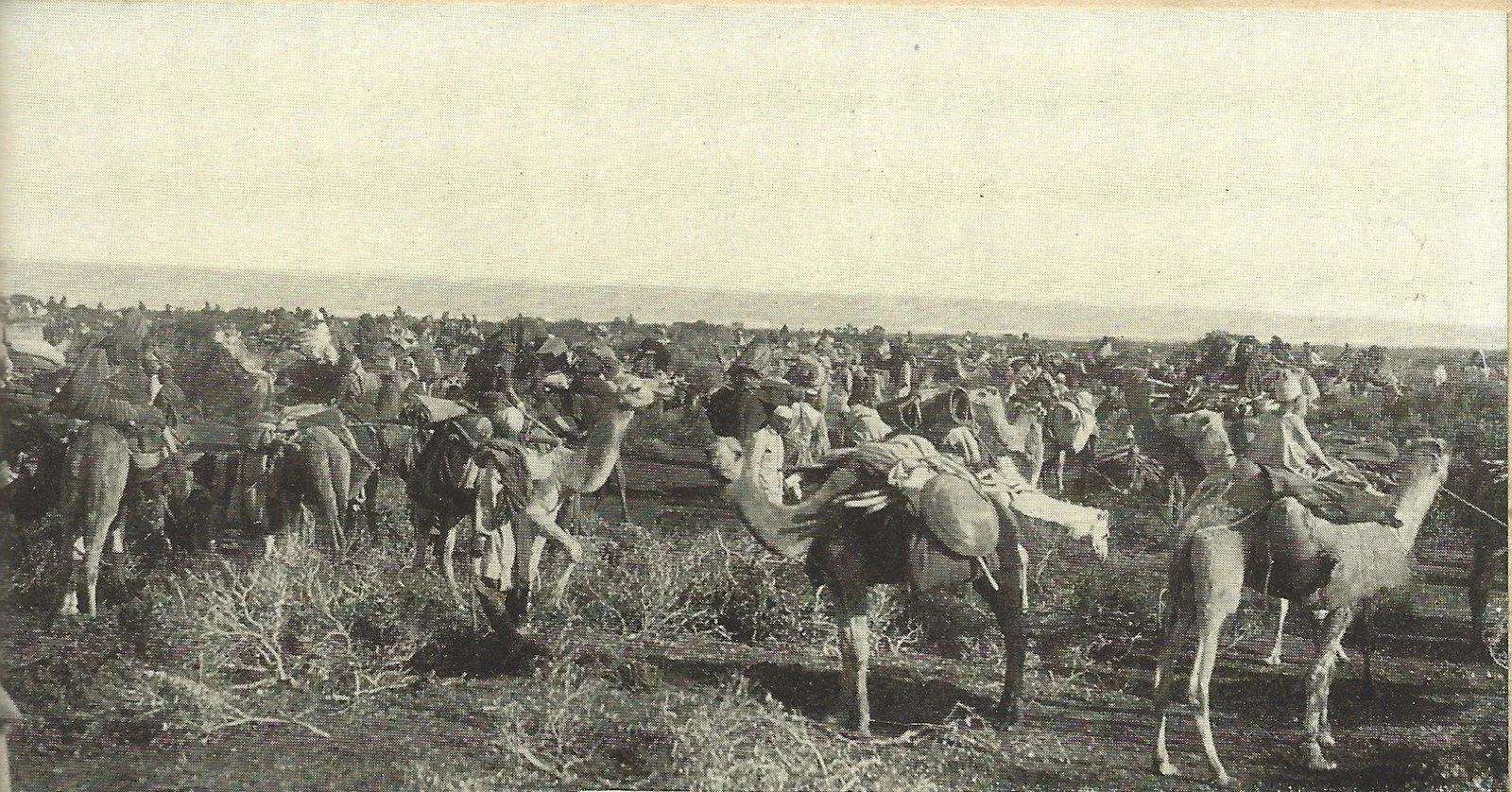

From 1930 onwards Graziani put his plans into action. Firstly, he made all forms of contact with the patriot forces a capital offence. The Italian military then instigated several disarmament campaigns against the local population, effectively disabling the rearmament of Omar’s men. Finally, and most brutally, Graziani approved the relocation of Cyrenaican bedouins to concentration camps situated on the coastal areas of Cyrenaica and Sirte, including Soluq (Soluch) just outside Benghazi which at one time had an internment population of over 20000 Libyans and Marsa el Brega on the coast of Sidra, which had an estimated internment of over 21,000.

A route within the Soluq (Soluch) concentration camp, which had circa 20.123 Libyan prisoners by 1931. Source: Rodolfo Graziani: Cirenaica pacificata. A. Mondadori, Milano 1932, p. 77.

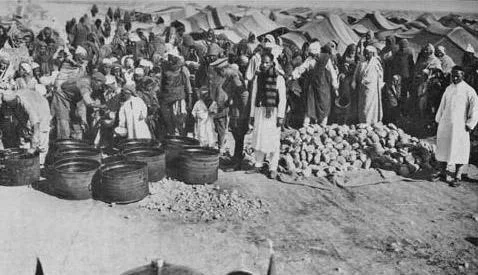

An estimated 110,000 civilians, mainly women, children and the elderly, and comprising a majority of the population of the Jabal Al Akhdar region, approximately half of the entire population of Cyrenaica, were forced to undertake a march from their homes into the desert where they were interned in concentration camps in the most horrific conditions8. The marcherThose who were too weak to keep up with the march and fell behind were shot: the majority of these being elderly and children. It is estimated that those who passed away in the death marches numbered in the thousands.

The camps constructed by the Italians were only capable of housing these captives in humane conditions, offering rudimentary housing and extremely poor sanitary conditons. Medical care was poor or non-existant, with the large camps of Soluq and Ahmed el Magrun having one doctor between them, whilst housing aproximately 33,000 captives in each. Typhus and other contagious diseases spread throughout the camps and the prevelance of skin diseases and virulent lice made daily conditions unbearable for the captives, who were already weakened from paltry food rations and forced labour. It is estimated that 44,000 of the interned Libyan population, close to 45%, had perished at the hands of the Italians by the time the last camp closed in September of 1933.

Photograph of Eritrean Ascari troops escorting the nomadic population during the forced march from the Jebel to Sirte from: Rodolfo Graziani, Libia Redenta, Storia Di Trent’anni Di Passione Italiana in Africa (Napoli: Torella, 1948)

Comnbined with those who perished in the death marches, it is estimated that between 60,000 and 70,000 Cyrenaicans perished during the Pacification of Cyrenaica9. Their livestock were also starved and died of diseases, resulting in a loss of over 600,000 animals10.

Deportation of Nomadic Tribes in Cyrenaica

Aerial View of Al Abiyar Concentration Camp

From 1930 to 1933, the Italians operated nineteen concentration camps in which the interned th tribes of Cyrenaica. All but one of these concentration camps were opened during 1930, that one being Abiyar which opened in 1931. Aqila was closed in 1932, followed in 1933 by the rest of the camps.

The 19 concentration camps opened in 1930 are Ajdabiya; Ain Ghazala; Sousa; Marj; Besher; Karakora; Kuifia; Derna; Deriyana; Noufliya; Qouarsha; Breyga; Magroon; Sidi Khalifa; Soluq; Swani Ikhwan; and Tikka. Abiyar was opened in 1931.

Photograph of an unnamed concentration camp in Cyrenaica, title ‘A Step towards Civilization’. Rodolfo Graziani: Cirenaica pacificata. A. Mondadori, Milano 1932.

Coefia or Kuifia Concentration Camp, which opened in 1930. From the Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Eastern Affairs, Rome.

Socio-Economic Impact of the Great Pacification of Cyrenaica

The social and economic subjugation of Libya during this period and throughout the colonisation was equally severe. With Italian businesses and families being inspired to settle in Libya, with the intention of further diluting the Libyan culture. Mass appropriation of land and the building of farms for the Italian settlers angered the Libyan population, who were also subjected to racial discrimination and segregation, with Italians enjoying privileged access to resources and services11.

Italian colonists on their way to Libya salute Benito Mussolini, Italy 1938

The colonisers exploited Libya’s natural resources for their own financial gain and ignored the needs and physical well being of the Libyan people12. They established plantations and mines to extract Libya's agricultural and mineral wealth, with the local population becoming a cheap supply of menial labour, often forced to work in these enterprises under harsh conditions and low pay. The profits from these activities were largely repatriated to Italy, with little benefit to the local population13.

Young Italian Colonists Take Break from Farming in Libya

Italian Colonist Family in Libya 1935

New land ownership rules and laws were introduced, which greatly favoured the Italian settlers and displaced locals, disrupting traditional livelihoods and weakening the fabric of their society. Italianisation was implemented with the suppression of indigenous cultures and languages, although they were still allowed to practise their own religion without interference. The imposing of taxes by the government, to fund projects that would only benefit the Italian settlers led to further economic disparities which perpetuated and promoted the deep resentment already felt by the indigenous people14.

These policies were to continue until 1943, when Libya was liberated from Italian colonisation by the British 8th Army.

Italian Colonists Off To Libya, 1930s.

FOOTNOTES.

E.E. Evans-Pritchard. The Sanusi of Cyrenaica. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1949. Pg.157.

Mann, Michael. The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2006. p. 309.

Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk. The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2010. p. 358.

“Second Italo-Senussi War.” Wikipedia, August 29, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Ital o-Senussi_War.

Pappé, Ilan. The Modern Middle East: A social and cultural history. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014.

E.Evans-Pritchard. The Sanusi of Cyrenaica. Oxford: University Press. 1949. Pg.187-188.

Grand, Alexander de. "Mussolini's Follies: Fascism in Its Imperial and Racist Phase, 1935-1940". Contemporary European History. 13 (2). Cambridge University Press. May 2004. 127–147.

Ahmida, Ali Alhamid. “ Eurocentrism, Silence and Memory of Genocide in Colonial Libya, 1929–1934.” The Cambridge World History of Genocide. Cambridge World History of Genocide. Volume 3. Genocide in the Contemporary Era, 1914–2020. Cambridge: 2023.

J.Wright. A History of Libya. Hurst & Co. London. London: 2012. Pg 148-149.

Ahmida, Ali Alhamid. “ Eurocentrism, Silence and Memory of Genocide in Colonial Libya, 1929–1934.” The Cambridge World History of Genocide. Cambridge World History of Genocide. Volume 3. Genocide in the Contemporary Era, 1914–2020. Cambridge: 2023.

Smeaton Munro, I. Through Fascism to World Power: A History of the Revolution in Italy. London: A. Maclehose & Co.1933.

Team, E. (2024, April 6). Italian colonialism in Libya. The Productive Nerd. https://theproductivenerd.com/italian-colonialism-libya/.

Ibid.

Ibid.